Early images from the Byzantine period are well renowned for their hyper religious imagery and symbols. Christianity had just replaced the myths of old as the “official religion” and the church were very keen to make sure everyone knew of it. Religious iconography was used in paintings as a way to both educate a vast number of illiterates about Christianity, as well as providing a gateway for the public to communicate with the saints depicted and pray to them. Many depicted the Madonna and child, some just the Christ figure, and many were emphasized with some sort of aureola, be it a religious glowing cloud, or just a regular old halo. (Halos are such an odd concept. We may be used to them now having seen them adorn every old religious painting for the past fifteen hundred years, but I wonder if people had any inclination as to what they were when they were first introduced. It seems a very abstract concept to depict someone important with an ominous golden circle floating above their heads.)

Although much emphasis was placed on the “return to classical art” the pictures often ended up looking very stylized (and sometimes a bit frightening) rather than the realism found in the greek style they were so influenced by.

Another thing about Byzantium art was that it was good at educating people. Before the time when anything was really written down, or people could read, pictures were used to teach the masses what would happen if they misbehaved. “The Damned are swallowed by a hellmouth” is an early example of this from around 1220, teaching that if you do bad things, you will most definitely be gobbled up by a large, pus green monster with a mouth filled full of demons, while the angel that you may have prayed to in your past life locks the door behind you and throws away the key. This type of cheery painting was commonly used by the church as a deterrent to control the actions of the masses through fear.

Although Byzantium’s political and religious influence spread far, it did not reach everywhere, and in contrast to these works, the Chinese landscape paintings of the same time are incredibly beautiful. The focus of these were obviously not on figures, and instead depicted mostly calming scenes of everyday life with focus on detail and beautiful linework.

The art which did feature people however was very different in that the subject was very rarely depicted as staring straight at the viewer, mostly without expression as was often the case in religious art. While Byzantium figures sit posed and lifeless the people in the Beijing Qingming scroll are facing away, animatedly going about their business, buying, selling, sailing down the river, one man seems to be putting on a jacket, making this look much more observational than the almost uncomfortable forced nature of the religious figures. There’s also humbleness, the people depicted seem to be quite ordinary yet it is still far more captivating. Zhang Zeduan’s scroll is also over 5 meters long, and every inch is detailed beautifully, this is another way in which it differs from Byzantine art, where scrolls eradicated in favour of the Codex, (an early bound book) which would be unable to capture the full scene in one go, especially not in such an awe inspiring manner as the scroll would.

Many copies have been made over the years of the Qingming scroll, each one using the same or a very similar composition, but adding “modern” features such as changing the architecture as seen in “Qingming shanghe tu” the Quing dynasty rendition from 1736, providing a detailed description of how the landscape changed over time.

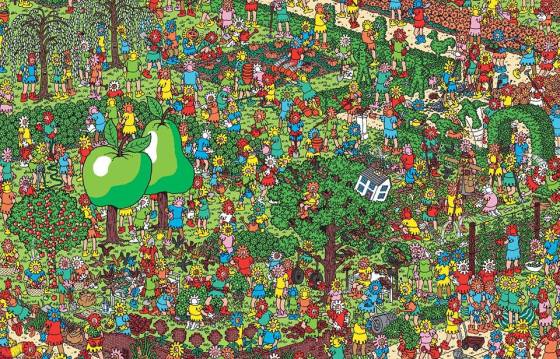

The scale of these paintings is impressive, and with the large detailed backgrounds and masses of small foreground characters all individually detailed and with such lively personalities, looks like it could have been one of the inspirations for “Where’s Wally?”

Qingming shanghe tu:

http://www.npm.gov.tw/exh96/orientation/flash_4/index.html

Star wars edition!

http://milnersblog.files.wordpress.com/2012/07/star-wars-celebration-vi-poster-by-jeff-carlisle.jpg

Sources:

Ebrey, B. “The Song Dynasty in China”

http://afe.easia.columbia.edu/song/ (30/11/2013)

Brooks, S. “Icons and Iconoclasm in Byzantium”

http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/icon/hd_icon.htm (October 2001)

Department of Asian Art, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, “Landscape Painting in Chinese Art”

http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/clpg/hd_clpg.htm (October 2004)

National Gallery of Art “Byzantine Art and Painting in Italy during the 1200s and 1300s”

![Gaddi- Madonna Enthroned with Saints and Angels [middle panel] 1380-1390](https://lmclaughhome.files.wordpress.com/2013/11/agnolo-gaddi-1380-90.jpg?w=560&h=489)